[MoCH] Bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki | 広島と長崎への原爆投下

•

by

•

by synhro

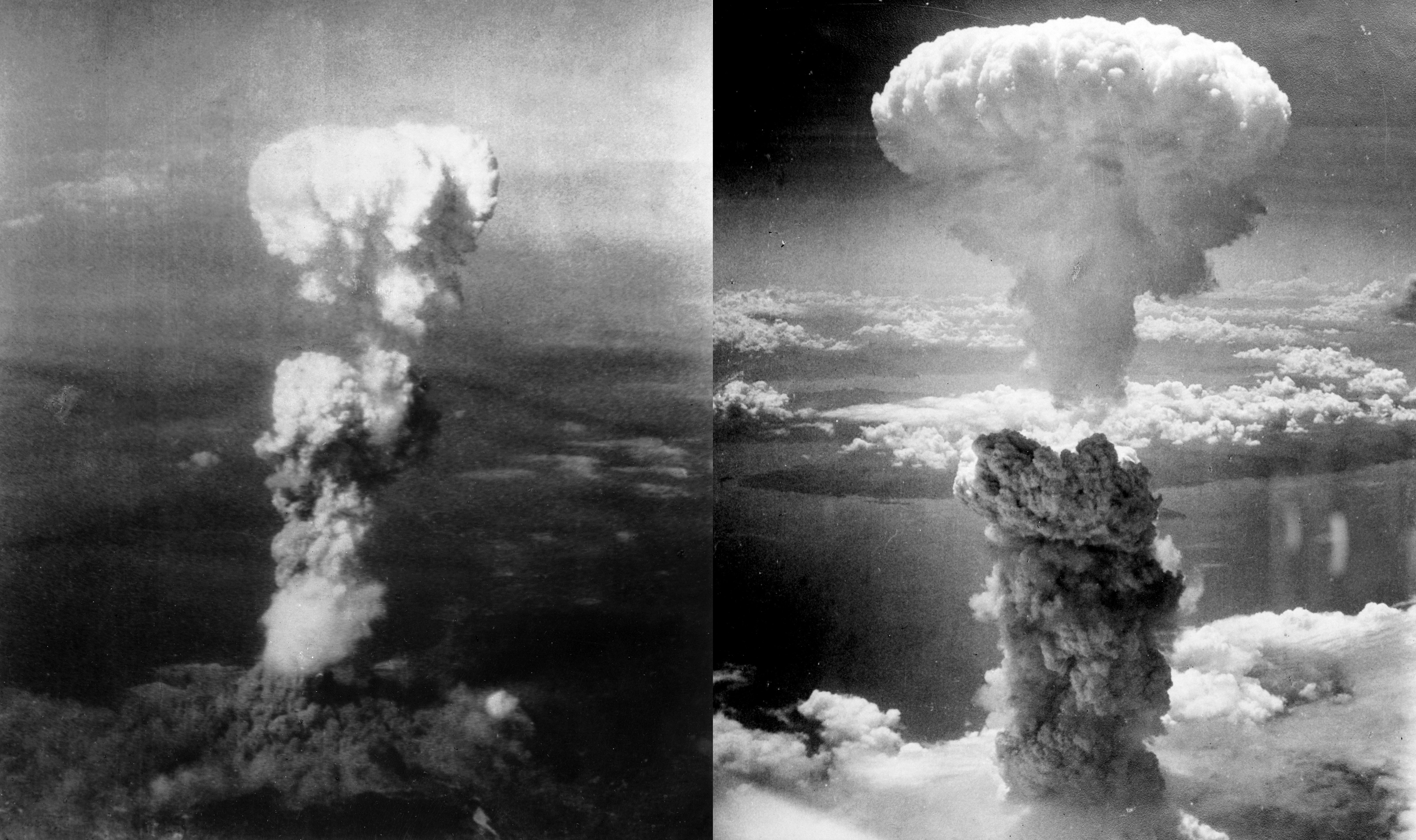

On August 6, 1945, during World War II (1939-45), an American B-29 bomber dropped the world’s first deployed atomic bomb over the Japanese city of Hiroshima. The explosion wiped out 90 percent of the city and immediately killed 80,000 people; tens of thousands more would later die of radiation exposure. Three days later, a second B-29 dropped another A-bomb on Nagasaki, killing an estimated 40,000 people. Japan’s Emperor Hirohito announced his country’s unconditional surrender in World War II in a radio address on August 15, citing the devastating power of “a new and most cruel bomb.”

The Manhattan Project

Even before the outbreak of war in 1939, a group of American scientists–many of them refugees from fascist regimes in Europe–became concerned with nuclear weapons research being conducted in Nazi Germany. In 1940, the U.S. government began funding its own atomic weapons development program, which came under the joint responsibility of the Office of Scientific Research and Development and the War Department after the U.S. entry into World War II. The U.S. Army Corps of Engineers was tasked with spearheading the construction of the vast facilities necessary for the top-secret program, codenamed “The Manhattan Project ” (for the engineering corps’ Manhattan district).

Over the next several years, the program’s scientists worked on producing the key materials for nuclear fission–uranium-235 and plutonium (Pu-239). They sent them to Los Alamos, New Mexico, where a team led by J. Robert Oppenheimer worked to turn these materials into a workable atomic bomb. Early on the morning of July 16, 1945, the Manhattan Project held its first successful test of an atomic device–a plutonium bomb–at the Trinity test site at Alamogordo, New Mexico.

No Surrender for the Japanese

By the time of the Trinity test, the Allied powers had already defeated Germany in Europe. Japan, however, vowed to fight to the bitter end in the Pacific, despite clear indications (as early as 1944) that they had little chance of winning. In fact, between mid-April 1945 (when President Harry Truman took office) and mid-July, Japanese forces inflicted Allied casualties totaling nearly half those suffered in three full years of war in the Pacific, proving that Japan had become even more deadly when faced with defeat. In late July, Japan’s militarist government rejected the Allied demand for surrender put forth in the Potsdam Declaration, which threatened the Japanese with “prompt and utter destruction” if they refused.

General Douglas MacArthur and other top military commanders favored continuing the conventional bombing of Japan already in effect and following up with a massive invasion, codenamed “Operation Downfall.” They advised Truman that such an invasion would result in U.S. casualties of up to 1 million. In order to avoid such a high casualty rate, Truman decided–over the moral reservations of Secretary of War Henry Stimson, General Dwight Eisenhower and a number of the Manhattan Project scientists–to use the atomic bomb in the hopes of bringing the war to a quick end. Proponents of the A-bomb–such as James Byrnes, Truman’s secretary of state–believed that its devastating power would not only end the war, but also put the U.S. in a dominant position to determine the course of the postwar world.

“Little Boy” and “Fat Man”

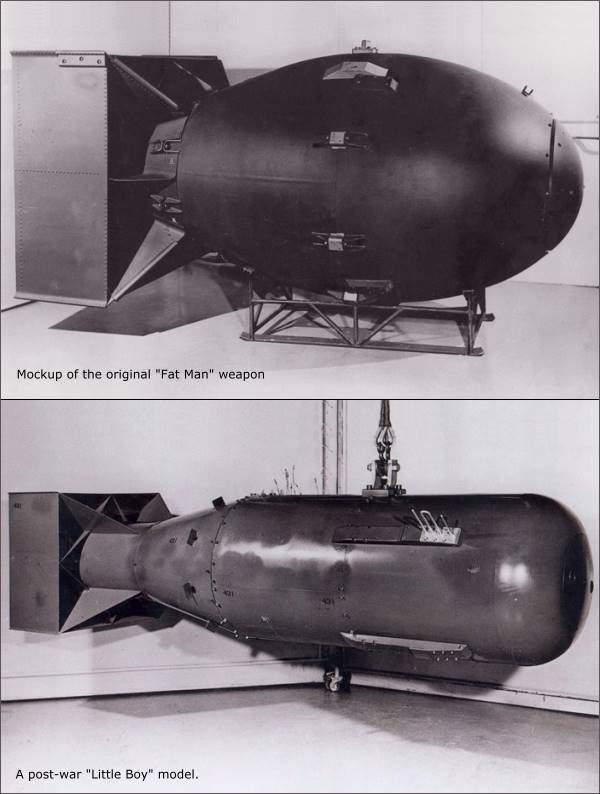

Hiroshima, a manufacturing center of some 350,000 people located about 500 miles from Tokyo, was selected as the first target. After arriving at the U.S. base on the Pacific island of Tinian, the more than 9,000-pound uranium-235 bomb was loaded aboard a modified B-29 bomber christened Enola Gay (after the mother of its pilot, Colonel Paul Tibbets). The plane dropped the bomb–known as “Little Boy”–by parachute at 8:15 in the morning, and it exploded 2,000 feet above Hiroshima in a blast equal to 12-15,000 tons of TNT, destroying five square miles of the city.

Hiroshima’s devastation failed to elicit immediate Japanese surrender, however, and on August 9 Major Charles Sweeney flew another B-29 bomber, Bockscar, from Tinian. Thick clouds over the primary target, the city of Kokura, drove Sweeney to a secondary target, Nagasaki, where the plutonium bomb “Fat Man” was dropped at 11:02 that morning. More powerful than the one used at Hiroshima, the bomb weighed nearly 10,000 pounds and was built to produce a 22-kiloton blast. The topography of Nagasaki, which was nestled in narrow valleys between mountains, reduced the bomb’s effect, limiting the destruction to 2.6 square miles.

At noon on August 15, 1945 (Japanese time), Emperor Hirohito announced his country’s surrender in a radio broadcast. The news spread quickly, and “Victory in Japan” or “V-J Day” celebrations broke out across the United States and other Allied nations. The formal surrender agreement was signed on September 2, aboard the U.S. aircraft carrier Missouri, anchored in Tokyo Bay.

Needless tragedy or prudent military decision?

Because of robust Japanese defenses and the topography of the islands themselves, an amphibious assault would have taken a heavy toll on U.S. forces. Military officials estimated that such an invasion might have incurred up to a million U.S. casualties, with corresponding Japanese military and civilian losses. Two fire bombing raids on Tokyo earlier in 1945 had already killed 140,000 citizens and injured a million more. The bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, then, might actually have spared hundreds of thousands of Japanese and American lives.

This justification, however, is not universally accepted. Some sources' estimates of U.S. casualties are significantly lower—perhaps as low as 50,000 men. It is also not entirely clear that an unconditional Japanese surrender was impossible, especially if Russia had entered the war before the bombing (Russia officially declared war on Japan on August 8, two days after the destruction of Hiroshima).

Some suggest that Truman, fearing a Soviet attempt to dominate the postwar Asian order as it had the Eastern European, ordered the bombing to force Japan's surrender before Russia had the chance to enter the fray (and thus earn the right to affect the peace settlement). Truman may also have wanted to intimidate his potential rival Stalin with the United States' new destructive capability.

Whether the bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki constituted a needless tragedy or a prudent military decision will never be certain. Those who made the decision, as well as most of the survivors, are long gone. The effects, though—the lingering scourge of radiation, the memory of the ghastly civilian casualties, the psychological impact of simply knowing that such a destructive force exists—remain. One can only hope that those who now wield the tools of armageddon will remember the lessons of Hiroshima and Nagasaki for a long time to come.

Your MoCH team:

Minister of Culture & History: Nanashi Senshi

Vice Minister of Culture & History: Turt037, sto kila bazuki

History Director: sto kila bazuki

Graphics Director: Turt037

Comments

[MoCH] Bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki | 広島と長崎への原爆投下

erepublik.com/en/article/2424341

One of the greatest genocides in the history of humanity, sadly still unpunished...

One of the greatest evils ever created.

Reading this while listening to Shiki-OST is epic

"If atomic bombs are to be added as new weapons to the arsenals of a warring world, or to the arsenals of the nations preparing for war, then the time will come when mankind will curse the names of Los Alamos and Hiroshima. The people of this world must unite or they will perish." - Oppenheimer

It could also be said that they are the greatest weapons of peace. Nuclear weapons killed traditional warfare and prevented a conventional war of attrition between superpowers. I'm not defending Nuclear armament, just playing devils advocate and saying what nobody wants to say.

Until WWIII starts, Nuclear weapons have eliminated war between major world powers and thus prevent millions of death....at the cost of constantly living with the thought that the world will soon be destroyed.

It could be said that are weapons of peace if innocent people weren't killed. Unlike the civilians of japan the soldiers are ready to die anytime if its for their country. Fine example for that were the Kamikaze (神風), for them it was honor to die for the country.

Nobody can argue about that the nukes have unintentionally become the most effective large-scale war deterrent, but calling them 'weapons of peace' is just an euphemism.

It just brought on a change of perspective regarding warfare..new war fronts are sneaky, underhanded, hypocritical with almost as many casualties (so far).

Call it what you will, the effect is what is in question. The reality of readily available weapons that can level whole cities, has inspired other means of combat for rivaling political ideologies.

And I strongly disagree with the suggestion that war has killed almost as many people as it would have without the invention of nuclear armament.

A ground war of attrition would have remained the global standard for solving political differences. 2.5% of the worlds population died in WW2. America would have invaded Moscow long ago if they didn't have nuclear weapons, and that would have ensured a long and bloody war of attrition. To illustrate American sentiment of the time, Gen. Patton asked Washington for permission to march on Moscow immediately following the fall of Berlin. Not to mention all the other inevitable altercations around the globe.

Modern warfare is fought with economics,far less bloody, and far more effective.

What to say about this that is not said before, pure demonstrations of power, case of vengeance and the end of a old and a beginning of a new era. We can only hope that something like this and the reasons and circumstances which lead to usage of this weapon never happen again, but seeing the current path of humanity and the proven fact that we never learn(ed) nothing from our past mistakes......nuclear war(s) will be the 3rd world war and who knows maybe The last war.

The USMC was being prepared for a ground invasion. In fact, the US created such a stockpile of the "Purple Heart" medal (given to US battle casualties) in anticipation of the cost of a ground engagement, that we still are giving out the medals made during WWII. Of like mind, the Japanese were training schoolchildren to Banzai charge Marines with Bamboo spears, should the US invade by ground.

In terms of total casualties, there is no doubt the atomic bombings saved millions of lives. In terms of morality, the demand of unconditional surrender prolonged the war and caused hundreds of thousands of deaths. The Japanese were willing to negotiate a truce, that was their primary objective after the initial land grab in the pacific.

On a personal note, I have seen both the Bockscar and (whats left) of the Enola Gay, seeing the planes illustrates a picture of a different era. They, along with the politics of the day, are relics of the past.

Also, living in New Mexico, I have been able to visit the trinity testing site (which is a part of white sands missile range). Some scientist wagered detonating the bomb would ignite the atmosphere and whether that would destroy the planet or just New Mexico.

At any rate, I am glad that we, as a race, can boast about still existing 69 years after the weaponizeation on nuclear fission (despite enough American and Russian nuclear stockpiles to destroy the world many times over).